How Maine Turned on Susan Collins

How Maine Turned on Susan Collins

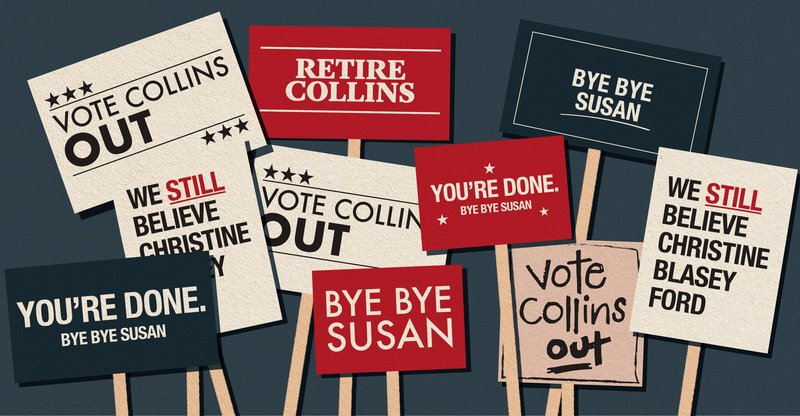

Inside the movement to topple the Republican senator.

By CHRISTINA CAUTERUCCI

SEPT 08, 2020

Six years ago, Karin Leuthy, a registered Democrat, voted for Republican Sen. Susan Collins. Like many Mainers, Leuthy, 48, took pride in not voting a straight party ticket that year. “I thought it was really important to have women in the Senate who were Republican, who were pro-choice, who would protect reproductive rights and be a check to the men in the Republican Party,” Leuthy said.

Leuthy lives in Camden, a coastal town with a picturesque harbor and a ski area that hosts a national toboggan championship every year. Her daughter raises sheep, which they board at a nearby farm. In 2014, when she last voted for Collins, Leuthy was an avid news consumer and regular voter, but not an activist. She admired Olympia Snowe, Maine’s long-serving Republican senator who retired in 2012 out of frustration with Senate partisanship. “Snowe was very thoughtful. She was straightforward. And she had a way of working in a diplomatic fashion that I think a lot of Mainers really appreciated,” Leuthy said. “I thought Susan Collins was going to serve in an Olympia Snowe model. I was very wrong. Very wrong.”

Ask a handful of Maine Democrats for their thoughts on Collins’ current reelection campaign, and you’re likely to hear at least a few stories that mirror Leuthy’s. At a late-February bean supper in Skowhegan hosted by Sara Gideon, the speaker of the Maine House of Representatives and now Collins’ Democratic challenger, I talked to more than a dozen attendees. Some lived in the 8,500-person town in central Maine; others had traveled to the steelworkers’ union hall from up to an hour away. They were mostly registered Democrats—some committed to Gideon, some still considering her primary opponents. Almost all of them had voted for Collins in previous elections. None planned to do so again.

In 2014, Collins won her fourth term with more than 68 percent of the vote. She won every county, every age group, every education level, every income bracket, and nearly 40 percent of Democratic voters. The next year, with a 78 percent approval rating in the state, Collins was ranked the most popular Republican senator. Back then, she enjoyed a reputation among many of her Democratic constituents as a prudent, upstanding moderate, a perception shored up by her occasional consequential swing votes that swung toward the Democrats. A regular stream of analyses named her the “most bipartisan” and “most disagreeable”—as in party-bucking—member of the Senate.

That picture of Collins, who was also named the Republican senator most likely to back Barack Obama’s positions, hasn’t always told the full story. The tallies that led to those titles include votes made only for procedural reasons and votes to pass Cabinet or judicial nominations, which Collins almost always supports, regardless of the president’s party affiliation. The bills she co-sponsors with Democrats—the ones that make her the “most bipartisan”—rarely make it to a vote. They often concern important but not particularly far-reaching or controversial issues: helping states build out broadband networks or reauthorizing a geriatric care workforce development program. Many peter out in committee, making them far more consequential to the co-sponsors’ respective bipartisan rankings than to the American people.

In the more consequential votes, Collins’ record has been mixed. She memorably cast a decisive vote against the GOP’s attempted repeal of the Affordable Care Act in 2017—but a few months later, she voted for the GOP tax bill that repealed the individual mandate. Collins opposed Betsy DeVos for secretary of education but only after casting an essential vote to send her nomination out of committee and onto the Senate floor. Collins made an eloquent defense of Planned Parenthood with her 2017 vote against the ACA repeal, then gave an equally impassioned speech in favor of Brett Kavanaugh, who’d go on to set the stage for a possible future rollback of abortion rights in his June Medical Services v. Gee dissent. She was one of just two Senate Republicans to vote in favor of allowing witnesses in Donald Trump’s impeachment trial but ultimately voted to acquit him, saying that Trump had learned an important lesson and would be “much more cautious in the future.” These actions have taken a toll: In January, Collins clocked in as the most unpopular senator, period.

Sen. Susan Collins at the Capitol on Sept. 26, 2018, the week Christine Blasey Ford testified against Brett Kavanaugh. Drew Angerer/Getty Images

Sen. Susan Collins at the Capitol on Sept. 26, 2018, the week Christine Blasey Ford testified against Brett Kavanaugh. Drew Angerer/Getty Images

Her bid for reelection, a foregone conclusion in previous years, is now a tight race. Since getting the nomination, Gideon has beaten Collins in every major poll, with independents and undecideds both leaning her way. Collins still has a chance to win—she’s the incumbent, and Gideon’s lead is not that large—but she’s going to have to fight for it. And the stakes are high: Collins’ seat is a linchpin of the Democratic Party’s plan to retake the Senate. Democrats need to win four Senate seats to gain a majority—three if Joe Biden wins the presidency—and Collins holds one of the seven Republican seats that look flippable. Only Sen. Martha McSally of Arizona is rated more vulnerable, according to the Cook Political Report.

That vulnerability points to something else happening in Maine, something that polling data can’t quite capture. In the years since Collins’ last reelection, Donald Trump’s presidency and the new left-leaning activist infrastructure that has sprung up in response to it have changed the state’s political landscape. Many Maine independents and Democrats told me they felt they’d been awakened from a period of political complacency—able to see clearly, for the first time, that Collins wasn’t the moderating force in the Senate she claimed to be. People like Leuthy, who had voted for Collins in the past, are now actively organizing against her.

______________________

The rest of the article can be found

here.